mTrigger biofeedback can be an excellent tool to help promote learning, proper movement, and increase muscle activation amongst patients. However, knowing when to first implement biofeedback, phase it out, or remove it altogether can be challenging. This is where the basic principles of motor learning can really help us identify and understand when it is best to use or remove mTrigger biofeedback during rehabilitation for ultimate learning and retention.

Learning can be defined as a “change in the capability of a person to perform a skill, inferred from a relatively permanent improvement in performance as a result of practice.”(1) Thus, if a patient is always solely relying on biofeedback during an exercise, they are not learning, adapting, or making the functional changes we are looking for. This is why when performing exercises with mTrigger biofeedback, it is important to remember the principles of motor learning and memory retention.(2) These aspects are critical to optimizing patient results and getting the most out of your biofeedback training.

When providing feedback to our patients, two big questions arise.(1)

- When do you provide feedback?

- How do you structure practice?

With this, there are several things to consider.

INTERNAL VS. EXTERNAL FOCUS OF ATTENTION

An internal focus of attention shifts the learner’s attention to an individual body part (ie: keep your knees apart) whereas an external focus of attention shifts the focus beyond the body (ie: press your knees towards the wall.”) During an exercise, using an external focus of attention can help to improve performance and skill retention.(3) mTrigger biofeedback provides an external focus of attention as patients focus on the screen’s activation meter to help improve muscle activation and movement patterns.

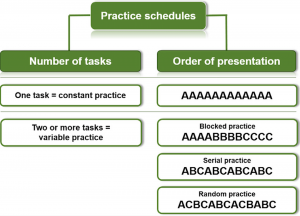

PRACTICE SCHEDULES

Part practice involves breaking down a skill into several fundamental segments. After mastering each part, the skill is put together.(1) This type of practice can be beneficial for novice learners or when an exercise is brand new to someone.(1) For instance, a sit to stand or a squat can be broken down into part practice to help a patient better understand and grasp the proper movement for each component.

A chair squat is an example of part practice. The patient is focusing on lowering down to the chair symmetrically without weight shifting.

Whole practice is when the entire exercise is performed in order.(1) This is a great way to promote more advanced learning for those with higher level skills.(1) Often times part practice is progressed to whole practice as a skill is mastered. For example, moving from standing up from a chair to a full squat.

PRACTICE CONDITIONS

There are three types of practice conditions to consider when teaching a motor skill. Blocked practice is when the same exercise is practiced and completed before moving on to the next exercise.(1) For instance, the patient performs three sets of bridges before moving on to three sets of squats, before finishing with three sets of step ups. Serial practice is when the same exercises are performed in the same order.(1) For instance, one set of bridges, squats, and step ups, in that order, repeated three times. Random practice is when a handful of exercises are practiced during a single exercise session in random order.(1) For instance, a patient performs one set of squats, followed by two sets of bridges, then back to step ups, before doing another set of squats, and finally back to step ups.

FEEDBACK SCHEDULES

When providing concurrent feedback to a patient, they receive feedback during the movement.(1) This is the type of feedback provided in the mTrigger “Train” screen. Early on in learning an exercise or a movement, this is the best type of feedback.(1) Here is an example of concurrent feedback using mTrigger.

Terminal feedback on the other hand, is provided only at the end of the exercise.(1) This type of feedback is great for the progression of motor learning and long-term retention.(1) This is the type of feedback you see in the mTrigger “Track” screen after the exercise has been completed.

It is important to start with more frequent feedback as a movement is being introduced. As understanding develops and progress is made, the feedback should be decreased (progressing towards terminal feedback) in order to help promote retention of learning.

In the second part of this blog we will discuss the impact of knowledge of results and knowledge of performance on motor learning as well as clinical applications for mTrigger biofeedback with all the covered principles.

SUMMARY

Utilizing motor learning principles is essential when it comes to maximizing the benefit of mTrigger biofeedback. Research has demonstrated that moving from part to whole practice, blocked to serial to random practice, and progressing from concurrent to terminal feedback with the use of external feedback must be incorporated to promote learning and retention of a skill or movement pattern.

Using mTriggers Audio Feedback Function

|

Reinforcing Movement Patterns with Biofeedback

|

References

1. Sattelmayer M, Elsig S, Hilfiker R, Baer G. A systematic review and meta-analysis of selected motor learning principles in physiotherapy and medical education. BMC Med Educ. 2016;16(1). doi:10.1186/S12909-016-0538-Z

2. Bade MJ, Christensen JC, Zeni JA, et al. Movement Pattern Biofeedback Training after Total Knee Arthroplasty: Randomized Clinical Trial Protocol. Contemp Clin Trials. 2020;91:105973. doi:10.1016/J.CCT.2020.105973

3. Sturmberg C, Marquez J, Heneghan N, Snodgrass S, Van Vliet P. Attentional focus of feedback and instructions in the treatment of musculoskeletal dysfunction: a systematic review. Man Ther. 2013;18(6):458-467. doi:10.1016/J.MATH.2013.07.002

4. Kaipa R, Mariam Kaipa R. Role of Constant, Random and Blocked Practice in an Electromyography-Based Oral Motor Learning Task. J Mot Behav. 2018;50(6):599-613. doi:10.1080/00222895.2017.1383226

Images: https://www.researchgate.net/figure/Types-of-practice-schedules-in-terms-of-number-of-tasks-practiced-and-orders-of-skill_fig2_281238061

Leave A Comment