As we look at the history of EMG biofeedback in this blog, we hope you can begin to understand the evolution of sEMG biofeedback in to practice. By taking a glimpse into the past, we can better comprehend the utility, importance, and viability of sEMG biofeedback in treating patients today. The history of sEMG biofeedback begins with the discovery of electricity and the invention of instruments that have allowed providers to see what they previously could not see, touch, or feel with their normal senses.

Historical Timeline

1600’s

In the 1600’s, Francesco Redi discovered that in an electric ray fish, the muscles were a source of energy.(1)

1700’s

Over a century later, John Walsh demonstrated an eel’s muscle tissue could generate a spark of electricity.(1)

The idea that a muscle elicits “electricity” was not new, however, it wasn’t until 1790 that scientist Luigi Galvani was able to directly show the relationship between a muscle contraction and electricity by demonstrating that a discharge of electricity could evoke a muscle contraction.(1)

Around the same time, physicist Alessandro Volta developed a tool that could stimulate a muscle using electricity.(1) This tool, similar to modern day e-stim, would quickly gain popularity, and provide a tremendous amount of a research into the function of the intact muscle.(1)

1800’s

In the early 1800’s the galvanometer, a tool for measuring electrical activity and thereby muscle activity, was invented by Luigi Galvani.(1) This really helped pave the way for the future scientific discovery of muscle activity.

Shortly after, researcher Carlo Matteucci demonstrated the link between an excited frog nerve and its connection to the muscle.(1) Following this discovery, in 1849, the first evidence of electrical activity during voluntary muscle contraction was demonstrated in human muscle.(1)

1900’s

During the 1900’s the discovery, research, and use of EMG biofeedback took off. First, in 1917, Pratt was able to show that the magnitude of energy associated with a muscle contraction was directly related to the number of individual muscle fibers being recruited.(1) Thanks to this and several subsequent discoveries, we finally understood that human movement was done under conscious control of the central nervous system.(2,3) Where the CNS systematically organized all the motor units necessary to produce the desired movement. When an injury, disease, pathology, or pain impacted this system, the pathway linking the brain and the muscle was disturbed.(3)

In the early 1920’s Edmund Jacobsen, a physician at Harvard University, is often credited with the first use of EMG as biofeedback for medical purposes.(1,4) Jacobsen used EMG equipment to monitor levels of muscle tension in patients with functional muscle disorders. He subsequently used it to provide biofeedback to those patients so they could work on gradually relaxing the involved muscles.(1,4)

After Jacobsen, physicians Alberto Marinacci and George Whitmore used biofeedback in the 1950’s to treat neuromuscular disorders such as stroke and spasticity.(4) At the time, sEMG was mostly being used for diagnostic purposes, despite evidence for its capability as a rehab tool.(4) It was quite a long time before the contributions of biofeedback for neuromuscular re-education took off again. This time, it was thanks to Herschel Toomin and Suzanne Owen and their work on sEMG for stroke rehab.(4)

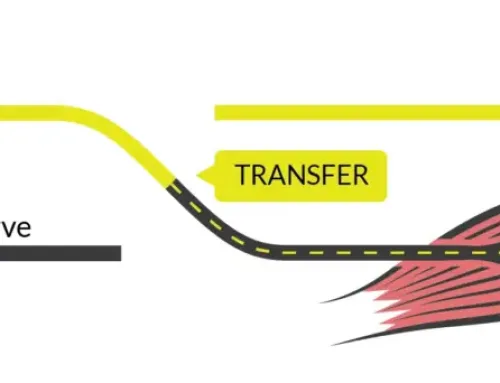

In the 1960’s the clinical use for biofeedback gained momentum and was utilized across a multitude of professions. For physical therapy in particular, biofeedback provided precise information about a patient’s physiological movements that then allowed the individual to establish better control over their body’s movement.(2) Biofeedback created an external feedback loop for patients that helped them improve their movement patterns by replacing the internal feedback loop they previously relied on following injury, disease, or pathology that led to their poor movement patterns.(2)

Finally in the 1980’s research began to strongly support the superior results seen with sEMG biofeedback in physical therapy.(1) Furthermore, as technology improved, better sensors, improved signal processing, remote communication, and 3-D displays improved the influence biofeedback had on rehabilitation.

sEMG Biofeedback Today

Thanks to the discoveries of those long before us, sEMG biofeedback has been used in physical therapy for over 50 years.(5) Combined with the providers knowledge and understanding of anatomy / physiology, sEMG biofeedback has a variety of applications spanning from assessment, treatment planning, evaluation of progress and outcomes, rehabilitation, worksite ergonomics, sports training, and research. The technology we have for sEMG biofeedback today, allows providers to differentiate between what they think they know about muscle function (observation) and what actual muscle function is occurring (objective data). Some of the most common uses for biofeedback include stroke rehab, motor dysfunction, muscle weakness, abnormal movement patterns, lack of balance/coordination, and postural steadiness.(5)

Surface EMG biofeedback takes physiological signals from the muscles and turns them into meaningful visual information to help patients develop control over their movements by bringing awareness to their muscle activation patterns.(4) Similar to how looking in a mirror allows you to see yourself, biofeedback allows patients to see inside their bodies and use that feedback to improve their muscle activation and movement patterns.(3) Furthermore, biofeedback training allows the individual to take an active role in their recovery as they work to developed a new skill instead of just passively receiving treatment.(3) This is one of the reasons biofeedback training is so successful.

Timeline of Biofeedback Research

Research supporting the utilization of sEMG biofeedback in physical therapy goes back decades. Looking at a timeline of the evolution of biofeedback studies, we see that it really starts in the late 1970s when biofeedback was initially used to help improve limb function, gait, and spasticity following stroke.(4)

Here is a video example of a patient using biofeedback today to help improve limb function following a stroke.

1980’s

A 1981 study following meniscectomy showed that when exercise was performed with the addition of biofeedback, EMG output of the quads was ten times higher.(6) Similarly, in 1983, the Journal of Physical Therapy and Rehabilitation published a study demonstrating isometric exercise with sEMG biofeedback was superior to isometric exercise alone for improving peak knee extensor torque.(7) Today, isometric knee extension is still a commonly used exercise to improve quad muscle activation and function following a knee injury.

Additionally, during the 1980’s, the use of sEMG biofeedback to record the symmetry of movement and address synergistic movement patterns such as the upper traps and lower traps during shoulder elevation was introduced.(1)

1990’s

Continued research on the use of sEMG biofeedback following knee injuries continued into the 90’s. Biofeedback was shown to improve the recovery time of the quad following ACL reconstruction surgery.(8)

Today

The evidence for sEMG biofeedback has expanded well beyond just the knee. Today biofeedback is used for low back pain, posture, hips, shoulders, knees, balance, stroke recovery, gait training, and so much more.

Summary

The evolution of sEMG biofeedback is extensive and fascinating. Thanks to improvements in technology and science, the use of biofeedback in physical therapy today is much easier and more readily available. The mTrigger biofeedback system is an excellent tool to begin incorporating sEMG biofeedback into your clinical practice.

mTrigger Biofeedback for Athletic Trainers

|

How Russ Paine uses mTrigger Biofeedback

|

References

1. Criswell E. Surface Electromyography. 2nd ed. Jones and Bartlett Publishers; 2011.

2. Moss D. Biofeedback, Mind-Body Medicine, and the Higher Limits of Human Nature. Humanistic and transpersonal psychology : a historical and biographical sourcebook. 1998;(January 1999):145-161.

3. Frank DL, Khorshid L, Kiffer JF, Moravec CS, McKee MG. Biofeedback in medicine: who, when, why and how? Ment Health Fam Med. 2010;7(2):85.

4. Peper E, Shaffer F. Biofeedback History: An Alternative View. Biofeedback. 2018;46(4):80-85. doi:10.5298/1081-5937.46.4.80

5. Giggins OM, Persson UM, Caulfield B. Biofeedback in rehabilitation. Journal of NeuroEngineering and Rehabilitation 2013 10:1. 2013;10(1):1-11. doi:10.1186/1743-0003-10-60

6. Krebs DE. Clinical Electromyographic Feedback Following Meniscectomy: A Multiple Regression Experimental Analysis. Phys Ther. 1981;61(7):1017-1021. doi:10.1093/PTJ/61.7.1017

7. Lucca JA, Recchiuti SJ. Effect of Electromyographic Biofeedback on an Isometric Strengthening Program. Phys Ther. 1983;63(2):200-203. doi:10.1093/PTJ/63.2.200

8. Draper V. Electromyographic Biofeedback and Recovery of Quadriceps Femoris Muscle Function Following Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction. Phys Ther. 1990;70(1):11-17. doi:10.1093/PTJ/70.1.11

Images

1. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Biofeedback

Leave A Comment