It’s easy to focus on how sEMG biofeedback helps increase muscle activation and improve movement patterns. However, there is a huge body of research to support its use for decreasing muscle activation as well.(1,2) In pathologies such as shoulder or knee pain, increasing muscle activation and re-enforcing proper activation patterns is key. Although this plays a role in low back pain rehab – and we will discuss that more later on – low back pain is often associated instead with excessive muscle activity.(1)

Many studies have shown increased lumbar paraspinal muscle activation in response to low back pain, as well as fear of low back pain.(3) When bending over, those with low back pain struggle to moderate muscle activation levels and tend to over activate the muscles along the back of the spine. Furthermore, they struggle to relax those same muscles once the task has been accomplished.(1,4–6) This constant state of over activation leads to dysfunctional movement patterns and increased pain. Those who struggle with back pain often have a difficult time relaxing and turning on/off muscles at the appropriate time. This is where visual biofeedback can be extremely helpful. Using mTrigger while performing standing lumbar flexion (see below for complete instructions) gives patients real time feedback on the intensity of their muscle activation and relaxation patterns during exercise.

Where to Start with Biofeedback

- Standing lumbar flexion and relaxation

-

- Using dual channel mode, place electrodes on the paraspinals: one channel on the right side and one channel on the left side.

- Instruct the patient to slowly bend forward, relax for several seconds, then return to standing.

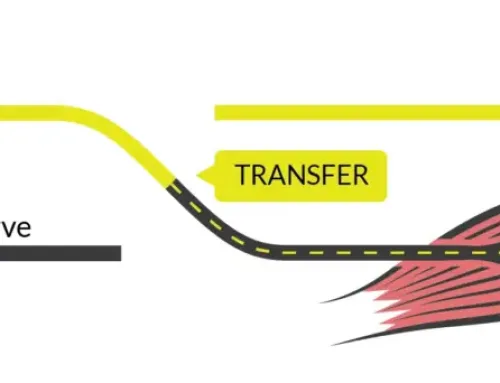

- During the motion, lumbar paraspinal activity will be high during the motion of forward flexion, however during the transition from forward flexion to relaxation, the patient is instructed to decrease the muscle activation meters of both paraspinals almost completely before returning to standing.

- Try repeating this exercise several times until the transition from flexion to relaxation becomes faster and smoother.

* This athlete, who is currently rehabbing for low back pain, does a decent job with this exercise.

-

Next Step…

After normal movement patterns are restored and pain levels begin to come down, the next step is to introduce some activation and strength exercises. As we have seen previously, low back pain elicits nonproductive, improper, and disadvantageous compensation patterns. As a result of this, patients with low back pain often demonstrate poor glute muscle activation and firing patterns as well as poor core strength and activation. Accessing the deep core muscles can be difficult and takes time; for many patients it is a frustration. While surface EMG is limited in this situation due to the deep nature of the transverse abdominus stabilizers, technology such as pressure biofeedback and ultrasound biofeedback are effective at monitoring transverse abdominus activation, moreso than verbal and tactile cuing alone.(7) After training and improving targeted abdominal activation, biofeedback resulted in better spinal stability and control during dynamic movements and general activity.(8) For more ideas on how to use surface EMG for improving core strength and stability, see our blog post here.

Getting More Advanced

An inability to activate the hip abductors and hip extensors is also a common flaw seen with low back pain.(9–13) The addition of specific hip strengthening exercises to a conventional rehabilitation program is beneficial for improving pain in persons with low back pain.(14) Kang et al demonstrated that you can further improve glute muscle activation with the use of surface EMG biofeedback during training.(15) The use of real-time biofeedback helps patients achieve better posture and improved muscle activation during hip abduction exercises.(15) Give this one a try:

- Hip Abduction

-

- Place the electrodes on the gluteus medius of the affected side using a single channel.

- Instruct patient to perform a simple hip abduction exercise (such as side lying hip abduction or a clamshell).

- As the patient performs the hip abduction exercise, they are instructed to increase the muscle activation meter as they start the motion, to hold the level of activation high throughout the duration of the exercise, then slowly lower down.

- As the accuracy and quality of movement improves, you can progress to more complex exercises (such as lateral band walks, running man, step up, side plank hip abduction, or a lunge).

-

Finally…

The ability to disassociate low back muscle (erector spinae) activation from glute muscle activation can become compromised with low back pain.(16,17) Often times, we see excessive lumbar spine and hip movement, including unwanted anterior pelvic tilt and lumbar lordosis.(16) Drawing in the abdominal muscles and stabilizing the spine minimizes these compensations.(17) If not trained correctly, it can easily seem like you are being asked to scratch your head and rub your belly at the same time. Thankfully, when supplementing exercise with EMG biofeedback, patients see instantaneously see whether they are activating their back or glute muscles during exercise and can make immediate corrections.

- Prone Hip Extension

-

-

- Place the electrodes on the lumbar paraspinals. Use dual channel: one pair on the right and one pair on the left paraspinals.

- Instruct patient to perform prone hip extension.

- As the patient performs the hip extension exercise, they are instructed to keep lumbar paraspinal activation low. As they extend the hip, the activation meter attached to the lumbar paraspinals should not drastically increase. If the meter does increase, the patient can see it and immediately make a change to the way they are performing the exercise (by shifting activation to the glutes).

- As the quality of movement improves, progress to more complex exercises (such as single leg bridge, deadlift, step up, single leg deadlift, etc.).

* This is an excellent example of the learning curve that occurs with biofeedback. Channel 1 is attached to her right glute med (want to see higher activation) and channel 2 is attached to her right paraspinals (want to see low level of activation). She really struggles at first but towards the end you can see her start to be able to lift her leg with less low back activation.

-

-

While this immediate biofeedback is critical in the early stages of motor learning, there must also be a transition to performing the movement with less cueing and feedback. For this particular athlete, we worked over the span of about 6 weeks to slowly remove feedback during the prone hip extension exercise. For the first two weeks she had constant feedback from mTrigger during prone hip extension and a few other rehab exercises. For the next 2 weeks she was performing exercises with feedback 1x/ week and on her own 2x/ week. In the final two weeks we randomly used feedback either during the exercise or immediately after the exercise using the “save session” function so she could view her results afterwards. During the last 2 weeks, we also began incorporating sport specific drill/skills for her sport (gymnastics) that utilized hip extension without lumbar extension.

This is how she does after 6 weeks of biofeedback training. No feedback and she does quite well!

Summary

Low back pain is a common and complex problem many people will struggle with at some point in their lives. Surface EMG biofeedback has an extensive list of uses for maximizing low back pain recovery. From helping to decrease paraspinal muscle over-activation, to improving muscle relaxation with daily tasks, to increasing muscle activation of the important core and hip stabilizer, the mTrigger biofeedback system is the versatile tool your rehab program has been missing.

How to get started with EMG

|

BFB for Spondylolysis

|

References

1. Nigl AJ, Fischer-Williams M. Treatment of low back strain with electromyographic bio-feedback and relaxation training. Psychosomatics. 1980;21(6):495-499. doi:10.1016/S0033-3182(80)73659-9

2. Jones AL, Wolf SL. Treating chronic low back pain. EMG biofeedback training during movement. Phys Ther. 1980;60(1):58-63. doi:10.1093/PTJ/60.1.58

3. Geisser ME, Haig AJ, Wallbom AS, Wiggert EA. Pain-related fear, lumbar flexion, and dynamic EMG among persons with chronic musculoskeletal low back pain. Clin J Pain. 2004;20(2):61-69. doi:10.1097/00002508-200403000-00001

4. Moore A, Mannion J, Moran RW. The efficacy of surface electromyographic biofeedback assisted stretching for the treatment of chronic low back pain: a case-series. J Bodyw Mov Ther. 2015;19(1):8-16. doi:10.1016/J.JBMT.2013.12.008

5. Pagé I, Marchand AA, Nougarou F, O’Shaughnessy J, Descarreaux M. Neuromechanical responses after biofeedback training in participants with chronic low back pain: an experimental cohort study. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2015;38(7):449-457. doi:10.1016/J.JMPT.2015.08.005

6. Neblett R, Mayer TG, Brede E, Gatchel RJ. Correcting abnormal flexion-relaxation in chronic lumbar pain: responsiveness to a new biofeedback training protocol. Clin J Pain. 2010;26(5):403-409. doi:10.1097/AJP.0B013E3181D2BD8C

7. Dülger E, Bilgin S, Karakaya J, Soylu AR. Comparison of two different feedback techniques for activating the transversus abdominis: An observational study. J Back Musculoskelet Rehabil. June 2021:1-5. doi:10.3233/BMR-200299

8. Southwell DJ, Hills NF, McLean L, Graham RB. The acute effects of targeted abdominal muscle activation training on spine stability and neuromuscular control. J Neuroeng Rehabil. 2016;13(1). doi:10.1186/S12984-016-0126-9

9. de Sousa CS, de Jesus FLA, Machado MB, et al. Lower limb muscle strength in patients with low back pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Musculoskelet Neuronal Interact. 2019;19(1):69. /pmc/articles/PMC6454257/.

10. Alsufiany MB, Lohman EB, Daher NS, Gang GR, Shallan AI, Jaber HM. Non-specific chronic low back pain and physical activity: A comparison of postural control and hip muscle isometric strength: A cross-sectional study. Medicine (Baltimore). 2020;99(5):e18544. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000018544

11. Arab AM, Soleimanifar M, Nourbakhsh MR. Relationship Between Hip Extensor Strength and Back Extensor Length in Patients With Low Back Pain: A Cross-Sectional Study. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2019;42(2):125-131. doi:10.1016/J.JMPT.2019.03.004

12. Peterson S, Denninger T. Physical Therapy Management of Patients With Chronic Low Back Pain and Hip Abductor Weakness. J Geriatr Phys Ther. 2019;42(3):196-206. doi:10.1519/JPT.0000000000000148

13. Cooper NA, Scavo KM, Strickland KJ, et al. Prevalence of gluteus medius weakness in people with chronic low back pain compared to healthy controls. Eur Spine J. 2016;25(4):1258-1265. doi:10.1007/S00586-015-4027-6

14. de Jesus FLA, Fukuda TY, Souza C, et al. Addition of specific hip strengthening exercises to conventional rehabilitation therapy for low back pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Rehabil. 2020;34(11):1368-1377. doi:10.1177/0269215520941914

15. Kang MH, Kim SY, Yu IY, Oh JS. Effects of real-time visual biofeedback of pelvic movement on electromyographic activity of hip muscles and lateral pelvic tilt during unilateral weight-bearing and side-lying hip abduction exercises. J Electromyogr Kinesiol. 2019;48:31-36. doi:10.1016/J.JELEKIN.2019.06.003

16. Oh JS, Cynn HS, Won JH, Kwon OY, Yi CH. Effects of performing an abdominal drawing-in maneuver during prone hip extension exercises on hip and back extensor muscle activity and amount of anterior pelvic tilt. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2007;37(6):320-324. doi:10.2519/JOSPT.2007.2435

17. Kim TW, Kim YW. Effects of abdominal drawing-in during prone hip extension on the muscle activities of the hamstring, gluteus maximus, and lumbar erector spinae in subjects with lumbar hyperlordosis. J Phys Ther Sci. 2015;27(2):383-386. doi:10.1589/JPTS.27.383

Leave A Comment